A performance video work shot in Shengzongsan Village, my grandmother's hometown in Feidong, Anhui Province. My grandmother's old home in the village no longer exists, but her distant relatives still live there. With their help, I symbolically reconstructed her house. This house was decorated and then deconstructed immediately after completion, leaving no trace.

All ten paintings and three performance works in Homecoming were made over one muggy summer in Hefei, China in 2019.

When I was one I was sent to live with my grandparents in Hefei for five years. During those years I formed a deep attachment to this older generation, a generation bearing witness to a rapidly-developing, ever-fluxing, endlessly-complicated China. Homesickness became a gnawing urgency, out of a desire to reconnect and to re-understand. In this body of work I am grasping at the boundaries of intergenerational disparity in Chinese society, linking these different eras through a life in China that is both real and imagined.

As a child of the Chinese diaspora, I have come to know myself to exist between ‘Asia’ and ‘the West’, in a space of in-betweeness that cultural studies author Ien Ang calls hybridity. I find myself at once defending China from the often misinformed and sinophobic Western eye, and cursing China for its many glaring flaws. The China I go back to is decidedly not the one from my childhood, although there are persistent traces of tradition. Despite relatively frequent visits, I had to come to terms with my feelings of lacking in Chineseness when in China. Ien Ang puts it aptly when she writes:

Diasporas are transnational, spatially and temporally sprawling sociocultural formations of people, creating imagined communities whose blurred and fluctuating boundaries are sustained by real and/or symbolic ties to some original ‘homeland’… It is the myth of the (lost or idealized) homeland, the object of both collective memory and of desire and attachment, which is constitutive to diasporas, and which ultimately confines and constrains the nomadism of the diasporic subject.

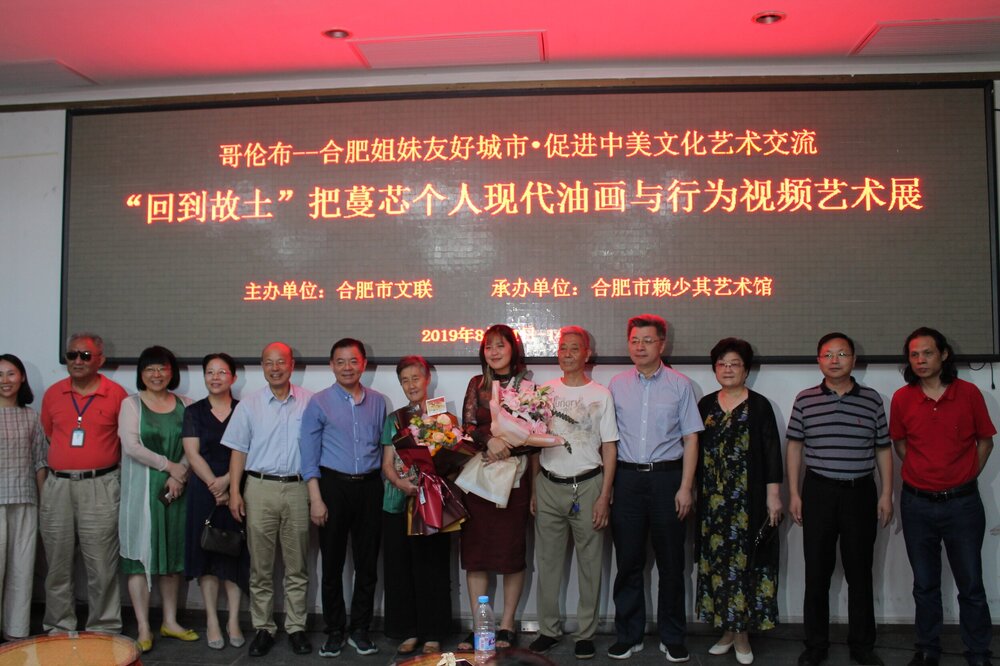

Homecoming was an exhibition, but it was also something of a performance. It became a literal homecoming—I was swarmed with local press, who were interested not so much in my artwork but in my backstory, which could easily be framed into something along the lines of “Chinese girl born in the USA loves her family and her homeland so dearly that she has returned to her homeland order to introduce her Western-educated art to her hometown!” As I was making the works and news of the show began to spread, I could feel the increasing pressure and expectation of this sentiment. In the end, it was the desire to grasp what is likely the only opportunity for my grandparents to see an exhibition of mine that overrode the many forms of quiet tension I felt while producing this body of work. For that, I would like to sincerely thank all of my family and friends in China for their support, and the directors at Lai Shaoqi Art Museum for granting me with this experience.

Young Grass

oil on canvas, 160 x280cm

How Long Does It Take to Eat a Watermelon (Short Film)

The habits of eating watermelon transcend across three generations of personal and national development in China.

The habits of eating watermelon transcend across three generations of personal and national development in China.

Full Table

oil on canvas, 160x260cm

Self Portrait with Red Dogs

oil on canvas, 150x120cm

福 (Fortune)

oil and paper cutting collage on canvas, 150x150cm

Family Pig

oil on canvas, 150x120cm

Trout Eaters

oil on canvas, 150x120cm

Dance

oil on canvas, 90x110cm

oil and paper collage on canvas, 80x100cm

I am jumping into a trout-farming pond during feeding time. This brief and spontaneous performance—recorded in Shengzongsan Village, my grandmother's hometown in Feidong, Anhui Province—acknowledges the class dynamics of agricultural labor and modern consumption.